Analyst, Measure Thyself

Using Jeopardy at-home scoring as a yardstick on my mental and physical health during chemotherapy treatment

Note: This post has to do with Jeopardy and statistics, but they’re all about me personally. If you’re looking for contestant analysis, this post isn’t going to touch that. But if you would like personal reflections and self-analysis centered on Jeopardy, read on.

It’s been a while, and that’s because I’ve been medically indisposed. The chemotherapy treatments that could last until sometime between May and August lasted until August – in fact, although I had my last injection two weeks ago, this is the last day of the additional pills for me. Although it was lousy in the (very, very long) moment to continue treatment, it’s for the best. My body held up well in the face of chemo’s ravages, enabling the lengthened preventative treatment and bringing down my risk of recurrence.

In the Jeopardy timeline, my chemo started not long after the Tournament of Champions was filmed and just a couple days before it started airing. I’d been able to attend a middle chunk of the tournament, but in my physically damaged state when the episodes aired I noticed that I was having trouble playing along even with games I’d seen in person. I didn’t keep score for myself through the TOC (because I’d seen some filmed) or JIT (because I didn’t need to feel worse than I already did), but I wondered what my scoring would be like when regular play resumed. I’d be almost done with the third three-week cycle of treatment, and maybe as well adapted as I could be to it. What would my performance be like in this state?

This dovetailed into other things I was thinking about. Cancer and chemotherapy are very personalized. There are things that are broadly true across patients, but there are many things that are idiosyncratic and individual. I had a broad idea of what would happen to my body under chemo before it started, but there were always things happening that were better, worse, or unexpected. Even early on, effects would vary from cycle to cycle. It was really hard to grapple with what was happening to me, and here was perhaps a way to put some numbers on it.

I resolved to score myself at home with the regular games once they resumed, and see if it told me anything at all.

How I Score Myself

Here is how I score at home, which is based on how I practiced with episodes between my first appearance and my TOC. Something counts as a response if I actually say the response before anyone on stage gives the correct response. Without the physical component, it’s too easy to fudge and say “oh I totally knew that” or “I didn’t actually get that wrong because I didn’t answer it.” I needed to hone my intuition about my own knowledge to reduce the number of passed-on clues without increasing the number of incorrect responses too much, and the only way to do that was to force out ambiguity. When I watch with my husband, I don’t give responses aloud because that’s rude, but I still mouth them for this purpose. In the past I’ve used index cards for manual scoring and then I used an app for a while, but with my reduced fine motor control in my hands and reduced mental energy I switched to just jotting things down in a big notebook of graph paper. Write down the clue value (divided by 100), put in a check or an X or a dash for how I did, circle the Daily Doubles, and maybe put diamonds on triple stumpers. Quick and easy in the moment and easy to use for tabulation later.

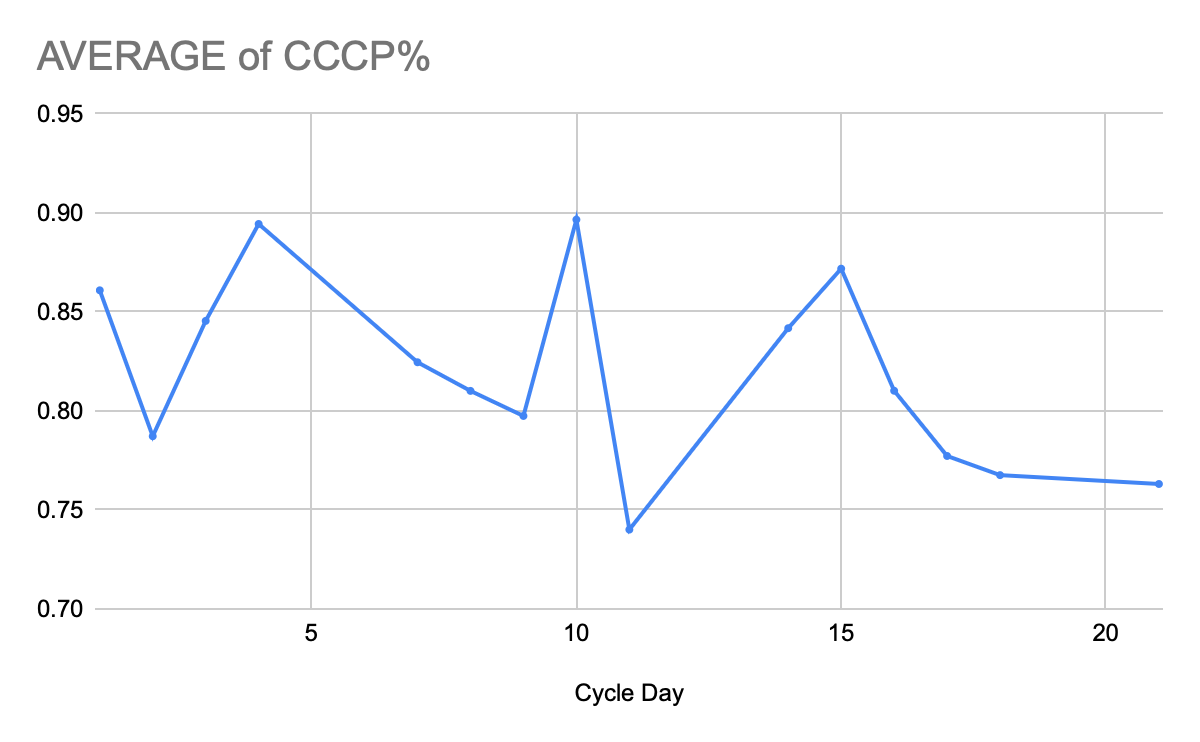

Although I can then keep track of both the number and value of correct versus incorrect versus pass (very important for training), my primary game-to-game statistic is CCCP%. CCCP stands for Combined Contestant Coryat Positive, and it is basically the combined Coryat scoring of the three contestants but without anything they miss. If you’re here maybe I should assume you know what Coryat is, but it’s a contestant’s score on the buzzer plus the face value of any Daily Doubles correct. No penalties for incorrect Daily Doubles, because you’re forced to answer.

CCCP is like if the three were playing as a team and had perfect knowledge of their own knowledge. This is the best easy thing I’ve come up with for gauging a game’s difficulty, and I compare my at-home Coryat score (including negatives for me) to that CCCP as a percentage. Should it be CCPC instead? The acronym meaning would flow better, but I enjoy the little history Easter egg.

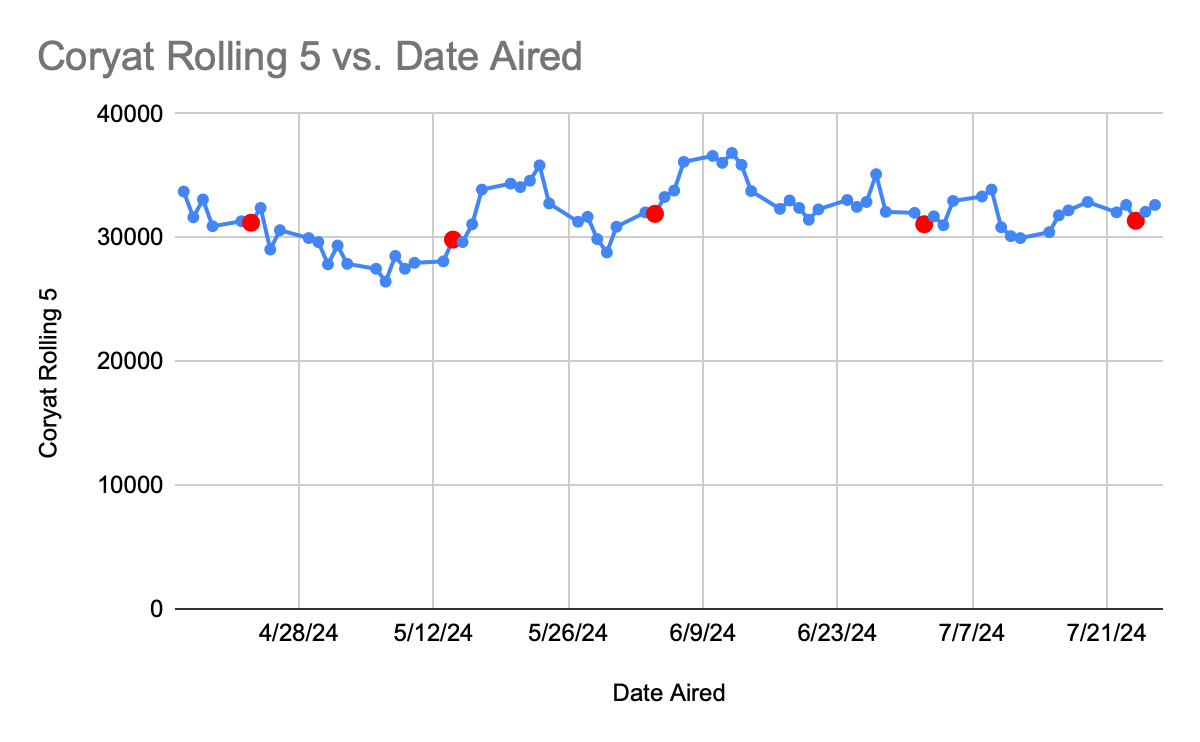

The last stretch of regular shows that I consistently scored myself on was April 12 to July 28, 2023, except for the month-long stretch from late May to late June when I was on the road. Over that time, my average CCCP% was 86.4% with a standard deviation of 15.1 percentage points. The raw Coryat average was $33225 with a standard deviation of $4542.

How I Scored On Chemo, Overall

I scored worse, but not by as much as I expected. From April 12 to July 26, 2024, my average CCCP% fell to 82.0% with a standard deviation of 13.2 percentage points. With the wide variation from game to game, putting this into statistical tests says that I shouldn’t reject that there is no difference in the scoring distribution from 2023 to 2024. It’s close, but I’m not going to tell you that anything I have in this post is statistically significant. It’s just pretty and maybe thoughtful. I’m an engineer, not a statistician.

It makes sense that the numbers fell, though. I felt worse, and I knew my mental capacity wasn’t all there. Every statistic you’d want to be high went down a little bit.

CCCP%: 86.4% ± 15.1% down to 82.0% ± 13.2%

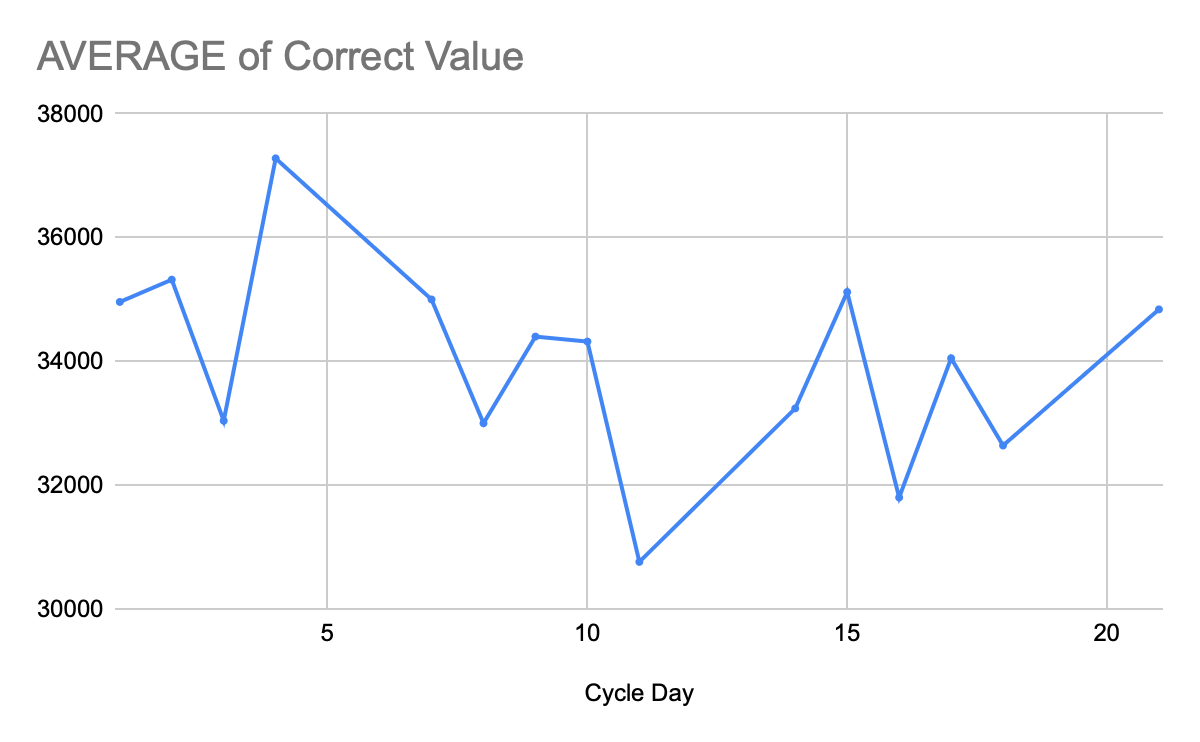

Raw Coryat: $33225 ± $4542 down to $31909 ± $4783

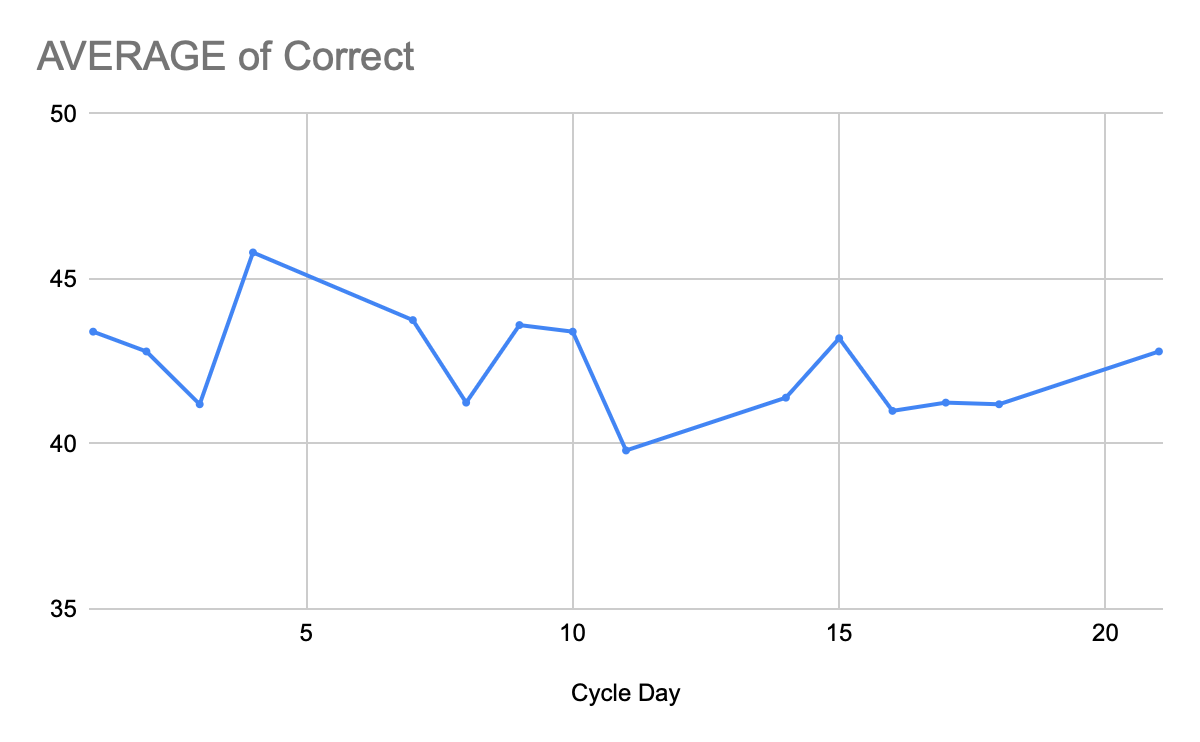

Correct responses: 43.3 ± 2.5 down to 42.3 ± 3.5

But I also knew that I felt worse at the beginning of each treatment cycle and better at the end, even somewhat normal. (My oncologist noted that this was incredibly positive news, even if that was the reason he recommended four more cycles than the original plan.) I wanted to know how I did through the course of each cycle.

Cycling

My treatment ended up consisting of eight cycles, all planned to be three weeks long. Day 1 of each cycle was a Tuesday, and I received a two hour IV drip of oxaliplatin. Each day from day 1 to day 14, I would also take capecitabine pills each morning and each night. During the first week of each cycle, I’d have neuropathy, cold sensitivity, bad body temperature control, little appetite, and low energy. I’d sleep a lot. During the second week, I’d start having enough energy to make it through the day, but only just. Most of the other side effects would lessen but not disappear. During the third week, I’d feel mostly normal, if still not as energetic as off drugs and with some neuropathy and cold problems, depending on the weather. After the fourth cycle, we reduced the amount of oxaliplatin I received by 20% because the neuropathy wasn’t wearing off much. The sixth cycle stretched an extra week because my liver enzyme count spiked. And I’m writing this in the middle of the eighth cycle.

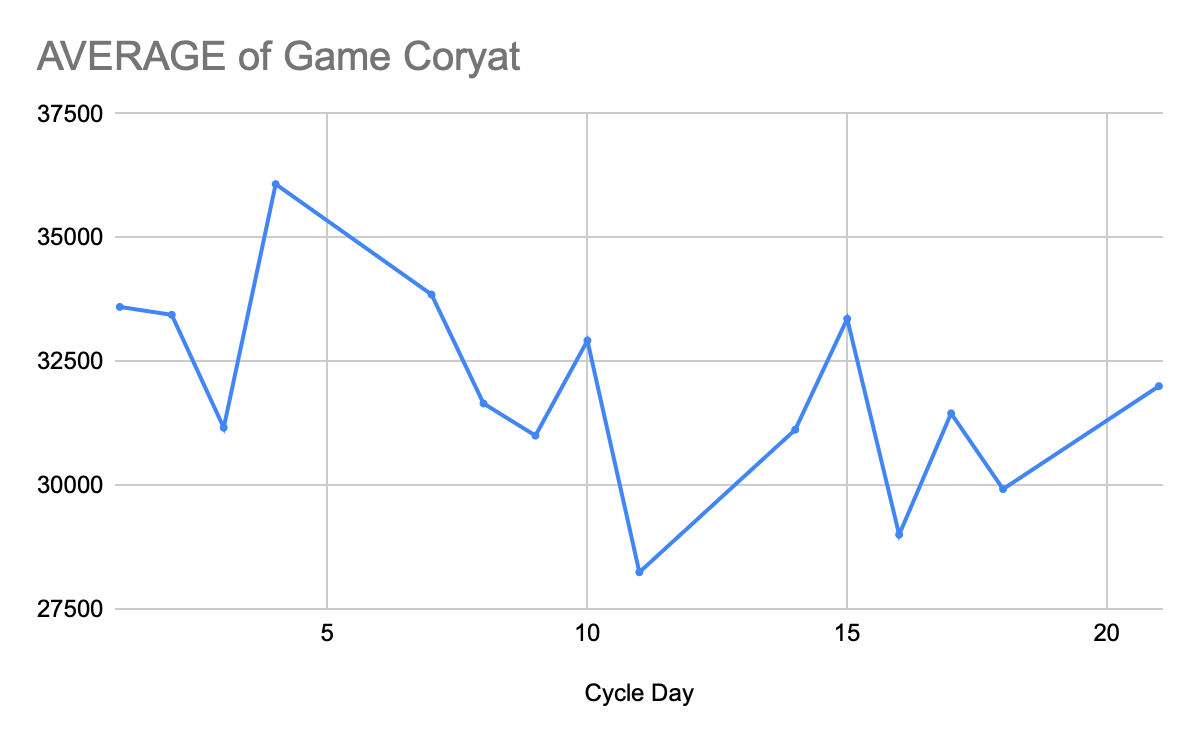

When I started score tracking, I was nearing the end of the Cycle 3, and my raw scoring got worse as the Cycle 4 started. Then it got worse still. I’d thought I’d improve later in each cycle, but it didn’t seem like it. Then I got my fifth infusion and my scores spiked up before settling down again later in Cycle 5. And then after the sixth infusion they spiked up again. What was happening in my brain?

I didn’t have an immediate answer for what was happening with the numbers within the cycle. But I did have an answer for why I was doing better generally starting from Cycle 5, and it was because I recognized the main reason I was getting answers wrong.

Adapting to My Mental State

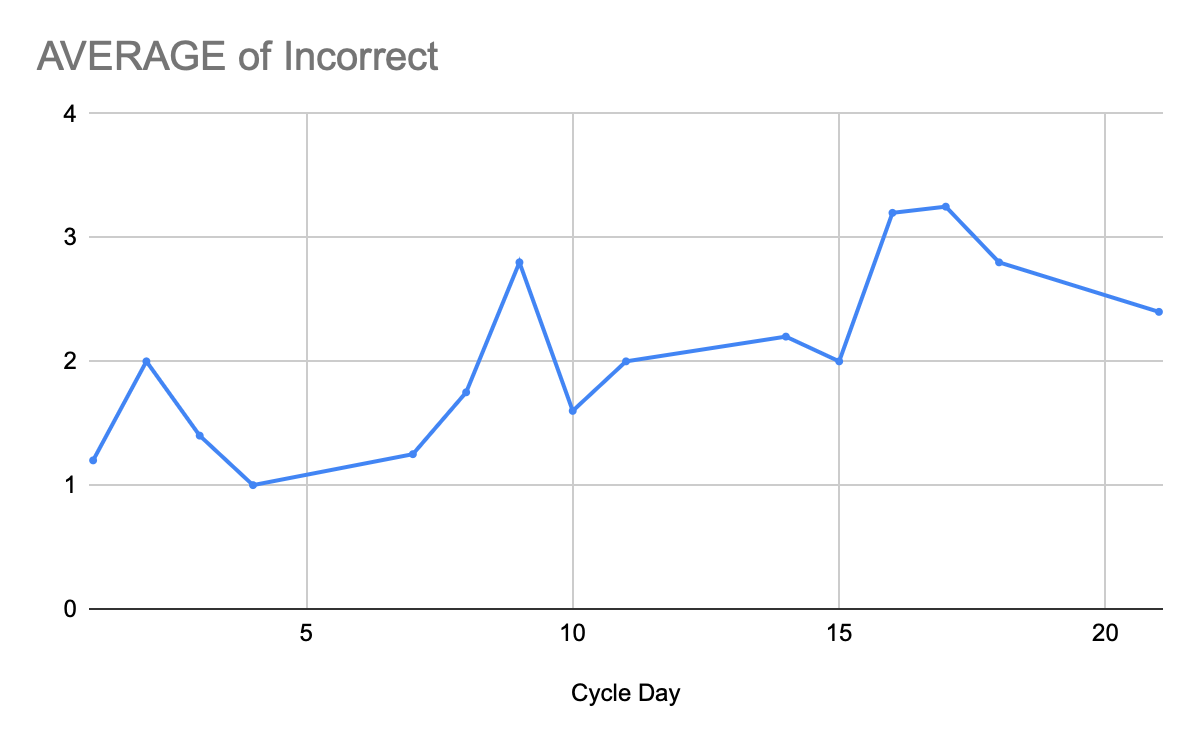

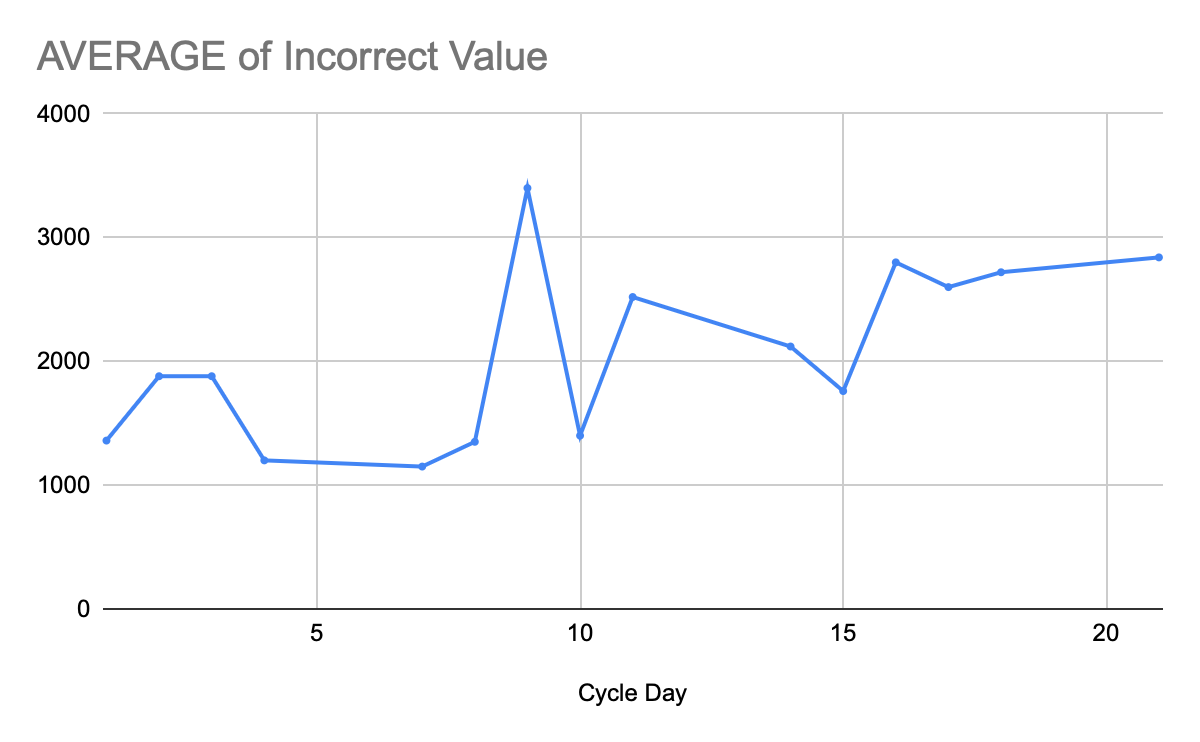

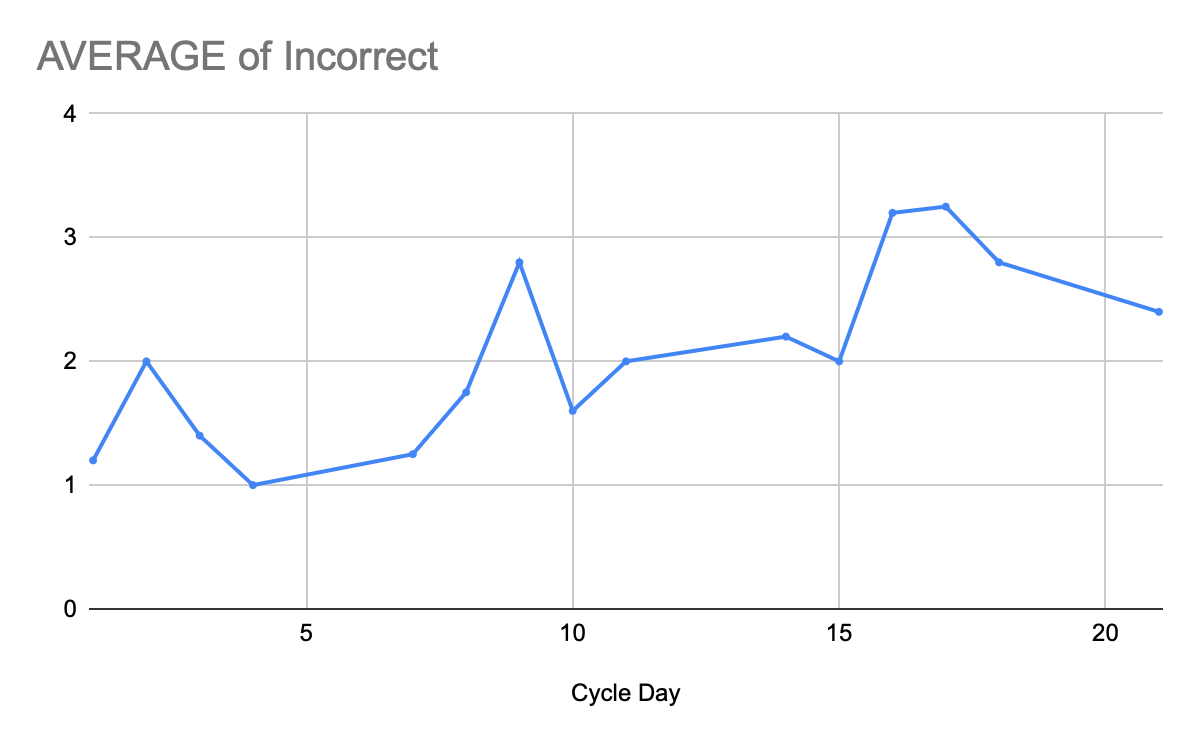

Up above, I didn’t include the comparison of my incorrect answers between 2023 and my 2024 chemo cycles because I wanted to get into it down here.

Incorrect responses: 2.5 ± 1.4 down to 2.1 ± 1.5

With fewer correct and fewer incorrect responses, I clearly passed on more clues in the 2024 chemo games. That’s because after Cycle 4 I assessed I was too lost to play accurately some of the time. A category would specify that responses start with “M” and I’d say “Houston” because I’d forgotten the category. I’d misparse clues and give information not asked for. Or I might just be slow in getting to a response, but my reactions and instincts have been built around the timing I had before, and I’d blurt something out without the full mental review it might have had. Incorrect responses were down in my chemo games overall, but during Cycle 4 they were up to 2.8 per game. I was losing an average of over $3000 in score each game. That’s actually okay under normal circumstances, but I wasn’t picking up enough correct to make up for it. I needed to adjust.

So I spent more mental effort on just straight up concentrating on the categories. I repeated them to myself as Ken read them. I might murmur a key part of it to myself when a contestant selected it. I’d never really had a problem with this before, and it put me off-balance. I’m used to bouncing and I can follow it – but not on chemo. Adriana Harmeyer’s streak included my peak performance at the beginning of Cycle 5, and I think it’s largely due to the top-down nature of her games.

I also recognized that sometimes it felt like I had an answer and I just didn’t. Every game felt like there were more things I knew but were just out of reach, and I only had the physical requirement of responding to keep me honest that I wasn’t getting there. I pulled back. I’d trained myself into aggression through 2021 and 2022, but now I needed to lay off a little. If I didn’t have something, or if I was stumbling in comprehension, I shouldn’t trust myself quite as much as before. My scores went back up as I trusted myself less. Not all the way, but up.

Not Adapting to My Physical State

Over time, that still left another question. Why was I doing better at the beginning of the cycle? Those were the times I felt the worst, and when I felt like I was thinking the worst. I’d started reading only books I’d already read, since the basic plot comprehension was already in my brain and I wasn’t getting that from new material. There were days when I couldn’t trust myself to write a coherent email. How could I answer rapid trivia?

The answer, I believe, is hidden up above in this post. In the first week, I could sleep eighteen hours a day. In the second week, I’d be more aware and awake, but I was still taking things easy. But in the third week, I was trying to live my life like normal. I was working full days, whether at home or at the office. (My immune system has not been so suppressed as to make that a worse idea than normal, though I remained cautious about crowded indoor spaces and masked. It helps that much of my workplace can be outside.)

I felt the scoring was telling me something important about my energy level. In that first week each cycle, playing Jeopardy might be not just the only mental effort of the day but possibly the only effort of any kind. In the second week, I was still more attuned to my body and taking naps or just checking out mentally in bed. But in the third week, I was exhausting myself. I could mostly make it through a normal day, but I had absolutely nothing left in the tank at the end. Some days I didn’t even make it that far. One day I realized I was tired at 4:15 in the afternoon and that if I didn’t leave right at that moment, the growing exhaustion and growing traffic would make it much more dangerous for me to drive home. I left, made it home feeling fine, and then immediately fell asleep for three hours.

If it was just the scoring, I might have written this off as too variable and paid less attention to it. But instead, the lower scoring was driven by an increase in incorrectness over the course of each cycle – exactly the problem I’d had in Cycle 4 overall. Even if I was doing better overall mentally and physically as the weeks progressed, the share of that going to Jeopardy was decreasing as I pushed myself to try to live normally.

I learned from this, too. Not in anything in playing Jeopardy, but in how I approached the last week or weeks in Cycles 6 and 7 (and 8, now starting). It’s reflected in my doctor’s prediction that I’ll still be lower in energy through all of August, even though I’m getting off drugs now. My body is going to feel better, and because it hasn’t felt better in a long time, that’s going to feel something like normal. But it’s not. I can still enjoy it for what it is, but some days you still have to give in and take a nap. I’m fortunate to be in a situation that accommodates that, and where I can do what I need to do to recover.

Self-Assessment

I’m not the player I was when you saw me on TV. I don’t think I’ll ever really be. I suspected before but more deeply understand now that I can play best when I’m in good physical and mental shape and also giving the game the bulk of my attention and energy. I filmed my first games in December 2020, the quietest possible time of year at work combined with being acclimated to the pandemic stresses of isolating – but before the ongoing stresses of reintroduction to the world. When I prepared for the TOC in 2022, I isolated at home for three weeks in preparation (I didn’t want to miss it!) and as a result ended up in a similar sort of mental and physical situation. If you watched that, you saw what I assume is my peak capability. It was a pretty good peak!

But I’m never going to replicate that sort of tranquil but focused state in my day-to-day life for the sake of playing Jeopardy at home. Lately, that day-to-day life involves getting pumped full of hazardous drugs that come with their own physical drawbacks. In the months to come, I have all sorts of other things demanding my attention: A new nephew. The baseball postseason. Finding my way back to the personal relationships I couldn’t handle while down for months. Continuing to get tested and monitored to catch any recurrence as soon as possible. Regaining normal neural feeling in my hands and feet.

But the energy will come back. I can be the at-home player I’ve been, and even now I’m almost as good. My ability to focus will come back, too. It’s just a matter of where it’s going to be pointed.

Special Thanks

I want to shout out that Jeopardy alumni are great people, and I’ve gotten so much support when I’ve needed it. One group I want to give great credit to my 2022 TOC friends, and in particular Brian Chang. Those of us who could make it to Culver City for the 2024 TOC had been excited to meet up again, to see each other and support the new set of players. The 2021 TOC crew had done this for us (after they played without audiences) and we wanted to replicate that. In the middle of that planning, I got my cancer diagnosis and had surgery. The taping ended up fitting in a small window where I was recovered enough from surgery to attend some of it but hadn’t started the chemotherapy yet.

Brian arranged to get shirts for everyone to show support for me, and he messaged my husband Jeff about it in secret to get approval. I had no idea until I got there, and it was overwhelming. In beauty, in kindness, in support, and in my own personal embarrassment. Brian told me that Jeff had said I would be fine with the display, and I must have looked a little skeptical because he amended that to “Okay, what he said was you’d be embarrassed but you’d come around and it would be good for you.” Which was 100% accurate, good on both of them.

The other group I want to specifically thank is the other alumni who are also survivors. I know that overall I’ve gotten off pretty lightly from the hands of cancer and chemo, but it’s still been a horribly rough nine months. Every positive step along the way has been rightly celebrated, every negative step has been met with empathy and the sharing of difficult experiences and thoughts (but not instructions!) on navigating just the worst stuff in life. No one walks alone, and I’m glad to have had them walk beside me… or maybe a little in front.

Appendix: Additional Graphs

Putting this complete set of graphs in wouldn’t fit well into the narrative as I wrote it, but I thought it would be nice to share anyway.